Kyle Davy and Mike McMeekin

According to author Peter Gleick, human history has been shaped by our relationship with water. Gleick’s recent book, The Three Ages of Water: Prehistoric Past, Imperiled Present, and a Hope for the Future, recaps this history. In the First Age of Water, early civilizations formed based on the natural availability of water, and the first attempts to control water for human consumption and agriculture were conceived. The Second Age of Water coincided with the emergence of science and technology and followed a “hard path” marked by the engineering and construction of major water-related infrastructure – dams, drinking water and wastewater treatment systems, hydro-electric generation facilities, and irrigation systems. This age produced huge benefits to humanity, along with unintended consequences in the form of withdrawals beyond natural recharge, pollution, and damage to eco-systems. In addition, despite the remarkable advances of the Second Age, we have still failed to provide safe water and sanitation for everyone.

In his kick-off address to Engineering Change Lab – USA’s (ECL) Envisioning a New Water Ethic for the Engineering Community Summit, Peter Gleick outlined the history of the first two ages of water and offered a blueprint for a hopeful future, a “necessary and possible transition” to the Third Age of Water. According to Gleick, this new “soft path” must:

- Rethink water supply – to include new advanced technologies, such as reuse of treated wastewater and desalination.

- Rethink demand – continuing the recent focus on conservation and efficiency that has seen recent declines in withdrawals even as GDP and population increase.

- See water as both a human right and an economic good and find the proper balance between both.

- Protect water quality and match the quality of the supply to the specific use.

- Protect ecosystem needs and health.

- Develop flexible water institutions that incorporate community participation and recognize the water / energy / food / climate nexus.

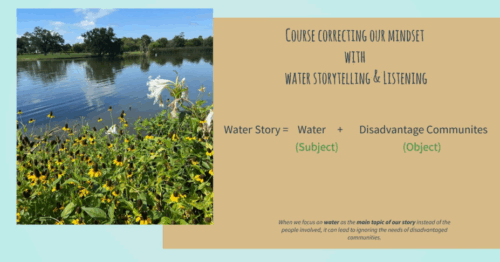

A key theme of the summit was the importance of hearing and understanding stories, both the stories of the engineering community’s role in the Second Age of Water and the stories of people’s relationships with water. According to summit provocateur Brittany Kendrick, our success in making the “necessary and possible transition” to the Third Age of Water will depend on a mindset correction in the engineering community in which we create new stories based on reverence for history and intentional listening to those impacted by our work.

In the first group exercise of the summit, participants explored the values and mindsets of the engineering community in the Second Age of Water. The dominant story of the Second Age was characterized by the creation of reliable and affordable access to water and sanitation services for those who can pay and by an engineering mindset of pride in both the creation of novel solutions for big infrastructure and in the ability to harness and control nature. The mostly untold shadow history of the Second Age includes the lack of access to water in undeveloped areas, forgotten people and ecosystems, and an engineering mindset of short-term thinking and subservience to political actors.

Summit provocateurs, Matt Thomas, an architect, artist, and community organizer from Taos, NM, and Robert Mace, of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, offered examples of their work in catalyzing a shift toward a water conscious culture. Thomas described his Paseo Project in Taos, which has used art and community engagement to create increased awareness of the ancient acequia irrigation systems in the area. The project has created shared experiences celebrating the acequia culture, bringing joy and happiness to residents, and strengthened an already strong local water ethic.

Mace highlighted the need to create awareness of water infrastructure, that is often distant from and unseen by the users of water. The Meadows Center does this directly by offering rides on glass bottom boats on Spring Lake (the headwaters of the San Marcos artesian spring in Texas) to view endangered species. Mace cited other examples of water reuse from Texas, such as rainwater capture and condensate harvesting from air conditioning, which are “local” strategies that both make water more visible to residents and provide a significant positive impact on water demand.

Summit participants then shared their own personal stories of consciousness around water. These discussions produced several important revelations.

- Personal experiences color our “water” stories and the intensity of those experiences can shape our beliefs about water. We need to expand our perspective by creating awareness of the experiences and stories of others.

- We take water for granted and communication about water is consistently lacking.

- There is a range of different relationships with water, and negative impacts such as fear of disease or fear of flooding create an increased awareness of water.

- Stories can help create connections between people and water and highlight the range of emotions that can accompany people’s experiences of water.

- Creating a community culture with respect to water is critical; we are all in this together.

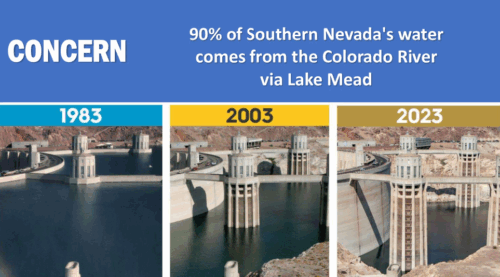

Provocateurs, Colby Pellegrino of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and Sarah Porter of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, continued the discussion of water culture and brought in aspects related to the true value (cost) of water. Pellegrino described elements of Las Vegas’ water conservation efforts, which have resulted in a reduction in water use by one-third over the last 20 years, while population has increased by more than 800,000 residents. These efforts combined a sound understanding of behavioral science and the economics of water (data and analytics) to influence and get buy-in from people in the community. Despite these major efforts, Pellegrino acknowledged that Las Vegas is not ready for expected future limitations on supply from the Colorado River.

Provocateurs, Colby Pellegrino of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and Sarah Porter of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, continued the discussion of water culture and brought in aspects related to the true value (cost) of water. Pellegrino described elements of Las Vegas’ water conservation efforts, which have resulted in a reduction in water use by one-third over the last 20 years, while population has increased by more than 800,000 residents. These efforts combined a sound understanding of behavioral science and the economics of water (data and analytics) to influence and get buy-in from people in the community. Despite these major efforts, Pellegrino acknowledged that Las Vegas is not ready for expected future limitations on supply from the Colorado River.

Porter offered two case studies related to water issues in Arizona and the true value of water. The first case study centered around Phoenix’s “next drinking water supply.” She related the history of development and water in the Phoenix area and the dynamics that unfold when different parts of a region have different types of water rights. One unanticipated consequence of these dynamics has been the ongoing rise in value of treated wastewater effluent, driven by the fact that effluent is the only water supply in that region that can be freely marketed – the entities that treat the effluent can do whatever they want with that water. She also outlined Phoenix’s future plans, which include a focus on advanced purified water (direct potable reuse) and establishing a $1 billion fund for imported desalinated water. Her second case study explored in more depth the complex ethical issues and potential dis-incentives that arise due to the regulatory boundaries that apply to Phoenix’s three sources of water (the Salt River Project, the Central Arizona Project, and groundwater).

Summit participants then began a discussion of the ethical dilemmas that will be inherent in the Third Age of Water. These dilemmas include issues related to balancing water usage between drinking water, irrigation, and ecosystems; re-thinking existing water laws such as those in Texas that allow unlimited pumping of groundwater; and utilizing “big” infrastructure versus more local or regional approaches. Each of these dilemmas will require the water engineering community to look for “both/and” solutions that capture the best elements of different approaches and to guide conversations with public stakeholders around these questions.

The second day of the summit began with provocations related to water insecurity and the needs of underserved communities from Brittany Kendrick of Black & Veatch and Amber Wutich, cultural anthropologist and Director of the Center for Global Health at Arizona State University.

Kendrick emphasized the importance of personal stories in collaborating with disadvantaged communities. She cited how the formal written narratives of these communities, as depicted in documents such as RFP’s, often fail to tell the full story and can express unconscious biases and assumptions about the people to be impacted by programs and projects. She offered three case studies of her work with disadvantaged communities, Muskegon, MI; West Holmes, MS; and Jackson, MS. A major lesson learned from her experiences with these communities has been that innovative approaches to community engagement that are based on oral narratives, intentional listening to personal stories, and reverence for the true history of the community, combined with equitable water financing, can produce positive outcomes.

Kendrick emphasized the importance of personal stories in collaborating with disadvantaged communities. She cited how the formal written narratives of these communities, as depicted in documents such as RFP’s, often fail to tell the full story and can express unconscious biases and assumptions about the people to be impacted by programs and projects. She offered three case studies of her work with disadvantaged communities, Muskegon, MI; West Holmes, MS; and Jackson, MS. A major lesson learned from her experiences with these communities has been that innovative approaches to community engagement that are based on oral narratives, intentional listening to personal stories, and reverence for the true history of the community, combined with equitable water financing, can produce positive outcomes.

Wutich began her provocation by highlighting “Day Zero” – the day in 2018 that the city of Cape Town, South Africa was projected to run out of water due to a severe drought. Cape Town narrowly avoided that crisis, but Wutich challenged the group that “it has been Day Zero in many communities around the world … for decades.” As an anthropologist, taking a 10,000-year perspective, she noted that water crises are not new and that we can use lessons from history to inform current responses to meeting the needs of underserved communities experiencing acute water shortages. Wutich described her ten years of work with disadvantaged communities in Bolivia, in situations where centralized, engineered water infrastructure solutions have failed. She related a key insight that when “big fixes” are either unavailable or have failed, people facing a water crisis decentralize. They fall back on their own “social infrastructure,” (social networks, informal economies, and social norms) to survive. She outlined how this learning is now being applied to disadvantaged communities in Arizona.

Summit participants used the practice of scenario thinking to look back from the future and explore the role of the engineering community can play in achieving equity in the provision of water and sanitation across the United States. This discussion was prefaced by the recognition that the forces that have produced inequities are still prevalent and increasing – deteriorating infrastructure and lack of maintenance, extreme weather, new water demand from emerging technologies such as AI, poverty and income inequality, and depopulation in rural areas. Significant insights from this discussion included the need for a holistic perspective and systems thinking, increased community engagement and collaboration, creativity and imagination that extends beyond the boundaries of economics (let art lead us), and viewing water as a “commons.”

Participants then continued the discussion of the ethical dilemmas associated with the transition to the Third Age of Water. This discussion centered on access to clean water and sanitation as a fundamental human right versus water as a commercial and economic resource. The discussion revealed that these ethical dilemmas are not addressed in our day-to-day work and that we often dodge discussions of these types of difficult issues. As we transition to the Third Age of Water, there was a clear consensus that the engineering community will need to educate and collaborate with communities and decision-makers to give greater priority to addressing these ethical dilemmas.

In the closing dialogue of the summit, participants considered the question, “What do we think we are learning about a water ethic for the engineering community in the Third Age of Water?” Important points that surfaced during the dialogue are highlighted below.

- Leadership from the engineering community is needed for the transition to the Third Age of Water.

- We have a responsibility to bring to light the ethical dilemmas that will form a new water ethic.

- The summit theme of storytelling is significant; listening to and learning from personal stories is a key element of leadership and stewardship.

- We need openness to “learning how to learn” in new ways, to thinking differently, and to dreaming.

- We need to create learning environments in our organizations and businesses.

- We must be empowered and have the courage to collaborate in new ways, and to push back, when necessary, with decision-makers. This empowerment begins with building trust and establishing relationships.

- Leaders’ actions must be rooted in humility, ethics, and community interests rather than in self-interest.

- The engineering community has an obligation to challenge the status quo, e.g., water laws.

- We can learn from the worlds of art and cultural anthropology how to collaborate in more effective ways with those who are impacted by our work. We should also celebrate clients and communities willing to take risks.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” Margaret Mead

There is no alternative to the “necessary and possible transition” from the Second Age of Water to the Third Age of Water described by Peter Gleick. Water is essential to human flourishing, and its future availability for all is at risk. The technical knowledge, experience, and relationships of the engineering community are components of the societal leadership that is needed for this transition. If those in the engineering community do not capitalize on these strengths, we run the risk of having future decisions imposed by others who have an incomplete perspective. This leadership can come in many forms and at multiple levels of society. What is most needed is that this leadership be inspired by a new water ethic, an ethic that recognizes that water is both a basic human right and an economic good, that we must protect the water needs and health of ecosystems, and that we must seek to expand access to clean water and sanitation to all. We must learn from the stories of the past to create new, positive stories in the future.

Provocateur presentations and recordings from both the virtual preview and the in-person summit are available at the Knowledge Hub Page of ECL’s website. Look for full documentation of the summit soon.