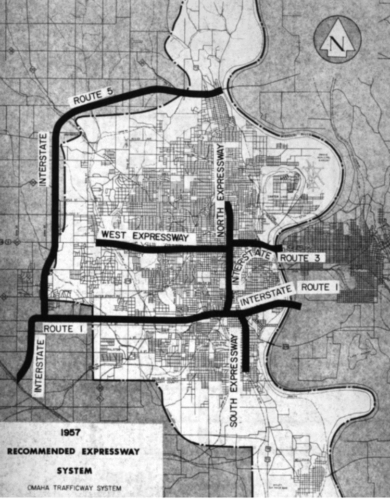

In 1956 President Dwight Eisenhower signed the historic Federal-Aid Highway Act that authorized construction of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, which came to be considered one of the United States’ greatest public works achievements. In Nebraska, the Department of Roads (NDOR) began planning for a state-wide system of freeways. Part of their planning included an expressway system for the Omaha area. The map shown below, from 1957, illustrates the “Recommended Expressway System” for Omaha. Several years later, NDOR modified this plan to include extending the North Expressway to connect with the expressway circling the northern side of the metro area.

The North Expressway, built in the 1960’s, bisected the predominantly African-American community of North Omaha. The West Expressway, along with the northern extension of the North Expressway, both of which would have cut through predominantly white neighborhoods, were never built.

The North Expressway was built despite major objections from the North Omaha community. The construction of the expressway resulted in the acquisition and destruction of more than 2,000 homes, churches, businesses and other structures and put in place a physical barrier that divided the community.1 It inflicted further damage on an area of the community that had been isolated from economic growth through red-lining. The North Expressway is one of many examples of infrastructure decision-making based on solving an isolated technical problem without consideration of the community impacts and, at its worst, represented blatant racism.

At the time of the planning of the Omaha expressway system, my grandfather was in a leadership position at NDOR, and my father was beginning his engineering career at NDOR. While I do not know my grandfather’s role in decisions related to locating the expressways in Omaha, there is a startling family connection to this example of the engineering community’s role in racial inequality.

Unfortunately, our history is full of examples of inequity in infrastructure, like Omaha’s North Expressway, and many of the inequities are racial in nature. Some of these racial inequities are highlighted in the book, The Sum of Us, by Heather McGee. In the book, McGee states that, “laws are merely expressions of a society’s dominant beliefs.”2 Laws and policies which govern our physical infrastructure have, at times, both fostered inequities and allowed them to continue to exist.

Swimming pools are an area of infrastructure inequities highlighted by Heather McGee. One of the impacts of desegregation in the mid-20th Century was that public swimming pools were opened to people of all races. In many areas, however, public leaders found ways to work around the desegregation of public facilities like swimming pools. Some cities converted pools from public ownership to private ownership so that segregation could continue. Other cities simply closed public pools, thereby denying access to all.2

Other inequities occur in housing and home ownership. Following World War II, federal investments in the highway system and other public policies spurred housing development in suburban areas outside of the traditional urban core. At the same time, racist public policy related to lending and covenants prohibited people of color from taking advantage of the suburban housing boom and the wealth-building opportunities that come with home ownership. The resulting segregation in housing still exists in most major cities, and the wealth gap that these policies contributed to still limits the areas where people of color can afford to live.

Throughout history, urban, minority neighborhoods have often been targeted for the siting of industrial facilities that exposed nearby residents to environmental and health hazards. These neighborhoods also often lack access to parks and open space. There is no more glaring example of this than in New York City. In the early decades of the 20th century, Robert Moses led the development of an extensive system of public parks on the outskirts of New York City and a network of parkways providing access to the new parks. Moses’ teams of engineers designed the bridges along the parkways with clearances that prevented buses from using the parkways thereby denying access to the minority communities that relied on public transportation.3

The engineering community is an important player in the systems that have created all these inequities. Engineers contributed to transportation and development policies, designed and built the highway systems and the segregated suburban communities that these policies produced, designed and built industrial facilities that harmed urban neighborhoods, implemented the racist infrastructure policies of Robert Moses, and stood by while swimming pools intended for the public good were restricted or completely removed.

One of the conclusions of Heather McGee’s book is that resentment of desegregation and civil rights policies is a factor that has helped to fuel the anti-government sentiment that has developed in the United States. This has contributed to societal divisions and our inability to unify around a common vision.2 This anti-government sentiment and division have extended to the under-funding of public infrastructure. In this sense, racism can be seen to be correlated with harm to the engineering community.

The racial influences on public infrastructure policy have been part of what McGee describes as a zero-sum way of thinking – that investments in the communities of people of color will reduce investments in other areas. The alternative way of thinking is to understand that shifting to an equitable approach to infrastructure investments will lift the economic output and social contributions of all parts of our communities, to the benefit of all. The engineering community, with our critical importance to the infrastructure of communities, stands to grow economically and in the public perception of our contributions with this shift in thinking.

ECL-USA’s next summit, The Engineering Ideas Institute II, will explore the history of engineering and infrastructure inequity and the ways the engineering community can adapt to correct current inequities and contribute to more equitable communities in the future. The summit will address key questions related to this issue.

- In what ways has engineering contributed to racial inequity in the U.S.? What issues continue to be present within and around the engineering community?

- What can the engineering community do to help heal racial inequality and create a more just, equal, diverse and inclusive society?

If you are interested in learning more about The Engineering Ideas Institute II or registering to be part of this summit, visit our website at the link below.

ECL-USA ENGINEERING IDEAS INSTITUTE

An important part of the vision for ECL-USA is to be a change agent, helping the engineering community to contribute at its highest level to the challenges of the 21st Century. Tackling the complex issue of racial inequality and engineering will be an important contribution to fulfilling our vision.

Notes

1 Adam F.C. Fletcher, “History of the North Freeway in Omaha,” October 28, 2020, History of the North Freeway in Omaha – North Omaha History

2 Heather McGee, The Sum of Us, One World, 2021

3 Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Vintage Books, 1975